The adjudication of sporting contests in New Zealand has its roots firmly in the foundations of the English legal system, where competitors (or competing teams) each appointed an “umpire” (or advocate), with both umpires then agreeing on a referee (or judge), in the event of dispute between them. In this respect, the adjudicating panel for a sporting event resembled that of "the courtroom". The model was particularly important in the early days of New Zealand where many sports (such as rowing, boxing, foot races and horse-racing) offered cash prizes to participants, often funded from spectator subscriptions.

Over subsequent decades, some sports have abandoned the referee in favour of umpires solely at the amateur level (for example, cricket and field hockey), while others have transferred the former power of umpires solely to the referee (for example, football and rugby union). In this regard, the terms “umpire” and “referee” have become somewhat interchangeable for those volunteering for the role of “match official”. Today, they are largely independent of (unaligned to) the clubs they officiate, with some (with prompting from high-performance promoters) fostering goals of becoming elite officials on the professional sporting circuit. On reflection, the loss of the direct connection between “club” and “match official” perhaps creates a tangible risk for the survival of all sporting codes at the community level.

If all sport clubs were obliged by their respective governing bodies to supply an appropriately qualified match official (either "umpire" or "referee") as a member of each team entered into a community competition (in the same way that teams in many sports are required to have accredited coaches), sporting codes may become better incentivised to promote and train volunteers through their network of community clubs. In turn, clubs and their members may then develop enhanced respect for match officials, based on their direct involvement in the development and support of their own. A further benefit would be an increase in membership of aligned organisations representing match officials. In New Zealand, some sporting codes have already adopted a version of this approach, but there is scope for more to be done.

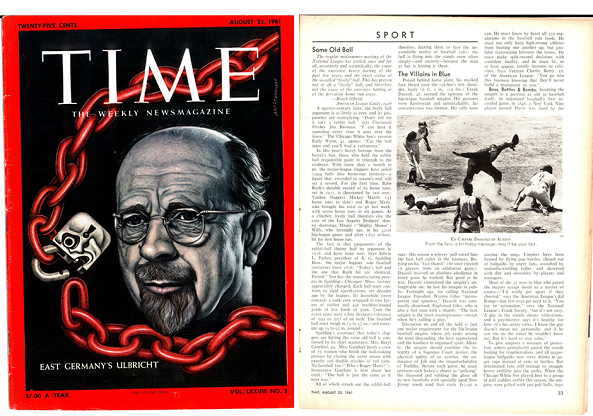

In August 1961, TIME magazine wrote “ideally, [an] umpire should combine the integrity of a Supreme Court judge, the physical agility of an acrobat, the endurance of Job and the imperturbability of Buddha.” While all of these idiomatic expressions will not necessarily be seen on a community sport arena in New Zealand, there is no doubt that the underlying qualities of "integrity", "composure", "endurance" and "fitness" are desirable hallmarks of all volunteer match officials, without whom amateur sport cannot survive.

The reality is that those who volunteer to adjudicate community sport should not be burdened with the expectation that their on-field performance should mirror the aspirations of those clubs and their players who strive to attain selection in elite sport. By placing more onus on community clubs to supply accredited match officials from within their own membership (as was the case in the past), a greater "love of the game" and respect for those "blowing the whistle", with all of their imperfections, will likely result. Moreover, by promoting the role of "match official" as a means to develop leadership qualities and community respect, there is a real opportunity to use amateur sport as a stepping-stone for building stronger communities.